Video games, whatever they may mean to you, are now a part of our shared heritage. At Press Pause to Reflect, we have strived to explore their value as such and come to a fuller understanding of our own, often confusing, culture. Bringing this blog to you for the past year has been a fantastic experience and 2010 looks even brighter. We couldn’t have done it without you, dear readers. Your comments and attention have kept us moving. We’d also like to thank the developers who took the time to talk with us about their experiences breaking ground in the medium. Keep up the good work, we will be watching with great expectation. And a big thanks to the welcoming world of video game bloggers. You’ve all been very friendly, helpful, and we’re grateful for every word and link. Please accept our warmest holiday wishes and best hopes for the new year.

Video games, whatever they may mean to you, are now a part of our shared heritage. At Press Pause to Reflect, we have strived to explore their value as such and come to a fuller understanding of our own, often confusing, culture. Bringing this blog to you for the past year has been a fantastic experience and 2010 looks even brighter. We couldn’t have done it without you, dear readers. Your comments and attention have kept us moving. We’d also like to thank the developers who took the time to talk with us about their experiences breaking ground in the medium. Keep up the good work, we will be watching with great expectation. And a big thanks to the welcoming world of video game bloggers. You’ve all been very friendly, helpful, and we’re grateful for every word and link. Please accept our warmest holiday wishes and best hopes for the new year.

Before we go on vacation, we’ve put together a little compilation of our favorite pieces from our first year as a blog. We hope you’ll look around, and that we’ll see you again in 2010.

Our Purpose

Playing with Art, by Daniel Bullard-Bates, and Josh Raisher’s follow-up serve as something like a thesis statement for Press Pause to Reflect, discussing the special merits of the video game medium.

Nostalgia

C.T. Hutt did some lovely pieces on the death of the arcade, difficulty levels in older video games, and just how much video game swordplay means to him.

Notions

Daniel offered some guidelines on how to extend game play without ruining the game and proposed an idea for a permanent-death horror game.

Complaints

Josh bemoaned the lack of permanence in video game death, C.T. complained about how abysmal the writing was in Gears of War, and Daniel whined that games are too in love with realism.

Praise

C.T. lauded environmental design in video games, Daniel got excited about writers doing a better job of injecting humor into games, and Josh exhibited an unhealthy obsession with Chrono Trigger.

Interviews

Tale of Tales, Jonathan Blow, and Jason Rohrer were all kind enough to answer our questions.

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Level Complete: 2009

Friday, December 18, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]: Game of the Year

by Daniel Bullard-Bates  Game of the Year: Flower

Game of the Year: Flower

In a year riddled with sequels and familiar, derivative material, Flower stands apart. This is a game that is more meditative than action-packed, and one that rewards a slow, patient approach. Instead of a space marine or a wise-cracking adventurer, the player takes the part of the wind, blowing petals from place to place. Besides originality in concept, Flower accomplishes something few games even attempt: it contains relevant social and political themes. Flower is presented with confidence and gravitas, delivering a message of change without a single word of dialogue. Remarkably, this message has the power to affect both the video game industry and the advancement of alternative energy.

Even the tone of the game speaks volumes for its creativity. It is at times exciting, but there is a quiet revolution here as well: the majority of the game is soothing. There are moments of adversity and triumph, but mostly there is just the peaceful exploration and transformation of wide expanses of land. In Flower, the world becomes more beautiful as you progress. Instead of leaving corpses in your wake, you leave blooming flowers and bright swathes of color.

Beyond Flower’s groundbreaking originality, it is spectacularly well-executed. The visuals are gorgeous, presenting one of the most colorful and dramatic landscapes of any game this year. The physics of the wind, carrying the many-colored petals and parting the grass beneath, help to deliver a sense of reality and immediacy to the game play. The world of Flower is transformed by the player, using the simple, proficient tilting of the controller, into a canvas of color and life. This is painting as performed by nature itself, placed in the palms of your hands.

Somehow, thatgamecompany has managed to create something fresh, beautiful and unique and get it right on their first try. There is not a single moment or mechanic out of place, the game never becomes dull or laborious, and the result is sublime. Other games accomplished a great deal this year: Uncharted 2, for example, took an idea that has been tried a hundred times and refined it until it shone. But what makes Flower the best game of the year is that it took an idea that was completely new, delivered on every possibility, and created something beautiful, simple, socially-relevant, and engaging. Flower is interactive art. And it feels so good.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]: Idea/Execution

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Best Idea without Execution: Scribblenauts

Best Idea without Execution: Scribblenauts

Scribblenauts is great for the first couple of hours. You can type in almost anything you can imagine, and a representation of that object will appear on the screen for you to interact with. The number of words that the in-game dictionary recognizes is stunning. Unfortunately, playing around with the dictionary may be the only really fun part of the game. Past the first few levels, the seams begin to show and then quickly unravel. The movement of your avatar is tied to the Nintendo DS stylus, causing him to throw himself into spikes just as often as selecting a usable item. This gets frustrating quickly, and could have easily been solved by using the DS buttons for movement.

Solving puzzles using all the items available to you should lead to a lot of eureka moments, but the objects interact in very limited ways. In one puzzle, when I was trying to move a cow so some cars could get by, I had the brilliant idea of using a shrink ray to shrink the cow, and then hiding it in a briefcase so that a nearby butcher wouldn’t see him. Unfortunately, the tiny cow wouldn’t go in the briefcase. (What? That was a reasonable solution.) Most puzzles ended up boiling down to just attaching something to a rope and a helicopter and moving it somewhere else. It’s disappointing that a game with one great mechanic failed to deliver a great game to surround it.

Best Execution without Ideas: Borderlands

Best Execution without Ideas: BorderlandsBorderlands comes from the Voltron school of game design: take several winning ideas from other games and properties, combine them into one unstoppable game/robot, and then publish. It is essentially the setting of Firefly or Mad Max with the regenerating shield of Halo, the shooting mechanics of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and the leveling and random loot system of Diablo 2 and World of Warcraft. The only thing that sets the game apart is that no one has ever made a combination quite like that before. Despite the lack of originality, those elements combine to make a fun, addictive experience that we can’t seem to shut up about.

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]: Single-Player/Multi-Player

by C.T. Hutt

Despite a plethora of high quality single-player experiences that have come out this year, Dragon Age: Origins reigns supreme. Single-player RPGs are designed to create the optimum mano-a-computer gaming experience, often without an online play aspect or offline cooperative modes, so it’s really no surprise that a title which has been crowned by many sources as the best RPG of the year also makes for the most engrossing single-player experience.

Stunning graphics, complex, strategic game play, and the engaging storyline offered by Dragon Age: Origins combine to keep any gamer with a taste for tactical combat and fantasy glued to their office chair for days. An outstanding single-player experience is not without its dangers of course. Side effects of Dragon Age: Origins may include: vitamin D deficiency, reduced social interaction, loss of sleep, carpel tunnel, poor diet, and delusions of being a Grey Warden. Other than those minor problems, we recommend Dragon Age: Origins to any gamer out there who wants to fly solo.

Honorable Mention: Batman: Arkham Asylum afforded gamers with an experience they have been anticipating for a very long time: a great game based on a comic book character. In some places Batman: Arkham Asylum went a little overboard (i.e.: chemical mega-joker), but it was still a fantastic title.

Most Engrossing Multi-Player: Left 4 Dead 2

Zombies. They stink, they try to kill you, and they drag down property value in a major way. As a responsible citizen and home owner it is your duty and your pleasure to shoot them in the head. But many hands make for light work, so while you are busy clearing the zombie infested streets of New Orleans from the undead, make sure to bring a buddy along. Left 4 Dead 2 brings home the awesomeness of a great horror/ survival FPS and an excellent co-operative game play experience. Nothing says “we are having some fun now” more than pounding your buddy on the back yelling “Shoot the the jockey! Shoot the jockey!” before you get pulled into a puddle of acidic spitter mucus. Toss in some excellent environments and a dash of poignant social commentary and you’ve got a title we will be playing for months to come.

Zombies. They stink, they try to kill you, and they drag down property value in a major way. As a responsible citizen and home owner it is your duty and your pleasure to shoot them in the head. But many hands make for light work, so while you are busy clearing the zombie infested streets of New Orleans from the undead, make sure to bring a buddy along. Left 4 Dead 2 brings home the awesomeness of a great horror/ survival FPS and an excellent co-operative game play experience. Nothing says “we are having some fun now” more than pounding your buddy on the back yelling “Shoot the the jockey! Shoot the jockey!” before you get pulled into a puddle of acidic spitter mucus. Toss in some excellent environments and a dash of poignant social commentary and you’ve got a title we will be playing for months to come.Honorable Mention: Borderlands. Wait, what? Didn’t you just say you hated that game? Not entirely. The setting, storyline, repetitive missions, character balance, and soundtrack of Borderlands all leave a lot to be desired, but the co-operative play is really quite good. Borderlands is proof positive that almost anything can be fun if you bring some friends along for the ride.

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]: Ambiance

by C.T. Hutt Best Ambiance: The Path

Best Ambiance: The Path

Tale of Tales has been the little game developer that could this year. They have turned the collective heads of the gaming community with their original titles and unique approach to the gaming medium. I haven’t had a chance to play Fatale, but if their past performance is any indicator of quality I am sure it will be a knock out.

The Path, released last March, is not what many gamers have come to expect from an exploration game. There are no traditional puzzles to solve in this game and no enemies to fight, but The Path manages to establish genuine emotional resonance with the player utilizing graphics tricks many would consider outdated. Ambiance in The Path is created by changes in camera angle, well-placed music and sound effects, and alterations in lighting.

There were few action-oriented components to The Path, which made the title a non-starter for many gamers. It was a game that focused on one central mechanic, our feelings about a given scenario, and didn’t let up. In many titles, ambiance and setting are obstacles developers work to overcome so they can get back into the action. In The Path, Tale of Tales made ambiance the whole point, and it worked.

Honorable Mentions: Flower and the Hard Rain level in Left 4 Dead 2 both had stirring ambiance. Whether eliciting an imprecise, but radiant sense of hope or simply evoking animal terror these titles used environment, sound, and music effects to their utmost. Worst Ambiance: Borderlands

Worst Ambiance: Borderlands

Following a compass needle through a vast junkyard in the middle of a desert, this is the Borderlands experience. I don’t have much to say about this title that hasn’t already been said. The action mechanics were spot on, but I simply couldn’t bring myself to feel anything but mild amusement from this game. They didn’t even get the feeling of desolation to ring through; in a game called Borderlands that seems like a necessity.

Monday, December 14, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]: Improvement

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Most Improved: Assassin’s Creed 2

Most Improved: Assassin’s Creed 2

Assassin’s Creed had a lot going for it: a conflict set in the middle east during the crusades, beautiful graphics and exciting assassination missions, but the game was bogged down by repetition and strange design choices. Fortunately, the developers at Ubisoft took almost every piece of criticism from the first game and worked it into the sequel. The mission structure became more varied, the settings became even more colorful, the main character learned how to swim, the player’s skills increased along with the character’s, and so on. Basically, everything Assassin’s Creed did, Assassin’s Creed 2 did better. The sequel still had a few problems (the free running system doesn’t always perform as desired and some of the mission types are still a drag), but the Assassin’s Creed series went from being a decently fun game with an interesting historical setting to a unique, exciting franchise in just a few years.

Honorable Mentions: Left 4 Dead 2 and Uncharted 2 both improved substantially when compared to their predecessors, but the first games in each series were already solid, so the change was not nearly so dramatic.

Least Improved: Overlord 2

Least Improved: Overlord 2

Seeing the progress made between Overlord and Overlord 2 was exciting at first. They improved the camera, gave the player more comprehensive control over their minions, and changed the morality system so that it encompassed two different kinds of evil, while the first one had a black and white morality. In the first game, I chose between giving the villagers food and keeping the food for myself. In the second, my options were killing all the villagers or bending their wills to my service. They even maintained the dark sense of humor from the original, which is a large part of what makes the series fun. Unfortunately, for every problem they fixed a new one popped up (just like playing whack-a-minion). While control of the minions was improved, the minions themselves seemed more idiotic and less likely to notice and interact with objects and enemies. The camera and the control mechanism were tied together, which resulted in the main character never looking where he needed to, resulting in irritating deaths and confusion. The morality system required the player to hunt down hundreds of individuals with no way to track them, which quickly became too cumbersome to be worth it, and the magic system was drastically over-complicated. I have a soft spot for both games, but Overlord 2 managed to make a mess just as often as it cleaned one up, resulting in a mediocre sequel to a mediocre game.

Friday, December 11, 2009

The 2009 Select [Button]

Don’t agree with our assessments? Tell us all about it in the discussion section.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Left 4 Dead 2: Left Deader

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

When Valve announced that Left 4 Dead 2 was coming within a year of the release of Left 4 Dead, I felt cheated and confused. Not only is that a quick turnaround time for any franchise, this is Valve we’re talking about: these are the same people who decided to do episodic content to make their Half-Life 2 releases come more quickly, and we’re still waiting for Episode 3, over two years after the last release in the series. This is a company known for taking their time to make sure the quality is up to their incredibly high reputation. Many people complained that Left 4 Dead 2 should be an expansion pack, and not a standalone game. But Left 4 Dead 2 doesn’t seem like an expansion pack at all. In fact, it makes the original look like a beta test.

Personally, I don’t imagine I’ll go back to the original Left 4 Dead after playing the sequel. Some of these additions are so obvious that they feel like they should have been in the first title: after the first time you run out of ammunition and switch to your samurai sword or fireman’s axe to fend off the zombie hordes, you’ll always want to have a melee weapon in hand. In Left 4 Dead, you would have been stuck with a pistol. The new massive zombie attack events that require you to run through an area to reach a goal are considerably more frantic and exciting than the numerous stand-in-place sections of the original. The AI director, which determines how many zombies attack and what types (and now even how parts of the levels are laid out), has been improved to the point that every safe house feels like it was hard won. This is surviving a zombie apocalypse done right. They even included an option called “Realism” mode, which removes some of the less immersive qualities of the game, like the outlines that appear to draw your attention to guns, ammunition, and your allies if they aren’t in your line of sight.

There are very few things to complain about. There is this incredibly irritating beeping noise which occurs whenever the game has some information it wishes to relay to you. I couldn’t find a way to shut this off on the Xbox 360 version. The only other concern I have is one of tone.

The first three levels of the game take place in very campy horror situations. The first is based around a mall, the second an amusement park, and the third a swamp. This makes for some fantastic set pieces and level design, but it feels out of sync with the last two scenarios, which both focus on much more relevant, socially significant settings. In “Hard Rain,” the players are in a rural town near New Orleans, walking through ruined streets and scavenging the contents of broken down homes. As the level progresses, the torrential rain becomes just as much an obstacle to progress as the zombies themselves. The streets become flooded, often blocking the means of escape. This leads directly into the final level, “The Parish,” where the survivors make it to New Orleans itself, where in the wake of devastating tragedy, a governmental organization (“CEDA”) is bombing the streets instead of working to rescue survivors. The early levels of Left 4 Dead 2 are a lot of fun, but “Hard Rain” and “The Parish” manage something considerably more impressive: they imbue a frantic action game with social relevance. They have something to say.

I wrote some time ago about how unrealistic and un-modern Call of Duty: Modern Warfare was, but this lack of social significance has not stopped the sequel from becoming the highest grossing entertainment launch of all time. It’s a strange day indeed when a zombie survival game brings more realism and relevance to the table than a series about supposedly realistic war.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

The Cutting Room Floor

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

With the advent of the DVD, it has become common practice to include deleted scenes with a movie. It is usually easy to determine why they were cut, whether it was due to the dialogue falling flat, problems with pacing, or simply because it was unnecessary to the plot or character development of the movie. Though it can be painful to amputate a scene that took a lot of hard work, the best directors know when to leave something on the cutting room floor.

It seems to be much more difficult for game designers to let go. Very few video games have no unnecessary sections, missions, or side quests. As Mitch Krpata points out in this post on Uncharted 2, part of what makes that game so fantastic is that there is so little fluff. But Uncharted 2 is the exception, not the rule, when it comes to game design.

Role-playing games provide some of the most blatant examples of unnecessary and unwarranted material. Often this superfluous content comes in the form of time-absorbing side quests. I understand the mentality that might bring a designer to include a few dull side quests: they’re entirely optional, so only the completionist will actively pursue all of them. I was once a completionist when it came to role-playing games, but pointless, hollow side quests have driven me to be considerably less thorough. Just because someone wants to experience everything a game has to offer does not mean that process should be completely mind-numbing.

There is one side quest in Dragon Age: Origins that asked me to collect twenty of a specific kind of mushroom. Here I am, trying to save the country and perhaps the world from an encroaching army of pure evil, and someone wants me to take some time off to practice amateur mycology. Even if this sounded like a fun pastime for my character, giving these mushrooms away for gold is completely counterintuitive to my character’s goals. These same mushrooms can be used to make useful potions to help in my battles against that evil army I mentioned. In other words, the task is boring and the goal is stupid. You get experience points for it, but how do I justify that to my party members? “I’m sorry you’re dying horribly because I traded in all those supplies, but I really wanted that next level up.” Most of the quests in Dragon Age can be completed on the way to more significant tasks or offer more substantial incentives for their completion, but a few should have been cut. Optional or not, boring gameplay is boring gameplay. I’m reminded of the uncharted worlds in Mass Effect.

Borderlands is a refreshingly straightforward game, in that it makes no effort to delude the player into thinking that there is some higher purpose to their actions. The goals are to find more loot and reach the next level, but this dull premise is redeemed by addictive gameplay and a fun co-operative element. This makes it easier to justify embarking on inane optional missions, since there’s no looming threat to make one hurry. Even so, some of the missions presented in the game are ridiculous even for a lowly mercenary. Shooting fecal matter off of a giant turbine does not make me feel cool. Collecting used smut magazines out of dumpsters is not an enjoyable way to spend my time. I don’t begrudge a game the opportunity to have a laugh, but joke missions should be brief so the joke doesn’t overstay its welcome. By the time I’ve trekked halfway across the map to find my third porn dumpster, I am no longer laughing. I am wondering why this made it into the game.

These are minor sins, since they can be safely ignored without detracting from the game experience. What’s even worse is when a game has required sections that are dull or counterintuitive to the game’s goals. In Assassin’s Creed 2, at several points the player is asked to tail someone, keeping an eye on them from a distance while they lead the player to a specific place. Get too close, and they will notice you, lag too far behind and you will lose track of them. This would be simply boring if they didn’t throw in multiple obstacles to your success. Guards along your path might recognize you, requiring you to blend with crowds or hire groups to distract them. This means that you spend large sections of gameplay just walking along watching someone else walk along, and if you don’t do just the right thing, you are noticed, which causes you to fail and start over. Suddenly they’re not just boring, they’re boring and irritating.

Sometimes, important plot information is being relayed by the people you are following. I appreciate the fact that these sections could be seen as a break from the running and jumping and killing, and it’s even a clever way to relay plot information without taking control from the player. But if those are the goals, why not remove some of the complications? Be more lax about the distances; remove the unnecessary barriers to completion. These are not difficult missions, so let them just be breaks from the action. I find it hard to believe that no play tester for Assassin’s Creed 2 turned to a designer and said, “This part is not fun.”

There are lessons to be learned from the cinema. If something isn’t working or doesn’t help a movie, a good director will cut it or edit it until it works. Most video games, even excellent ones, have sections that should have been left on the cutting room floor. Maybe they just need harsher editors.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Tick Tock

Bowser, King of the Koopas, likes to think that he is the most dangerous thing in the entire mushroom kingdom. He controls legions of baddies, reigns over the land in a castle of darkness and fire, and can kidnap a princess with the wave of a claw. But for all his bluster, Bowser is a lightweight in comparison to the deadliest device Mario ever faced: the ticking clock.

I remember the very first time I played Super Mario Brothers I was so enchanted by being able to control my little avatar on the screen that I didn’t pay attention to the time. After my 399 seconds had elapsed, Mario suddenly died. When I asked my mother why, she calmly informed me that after the time ran out the bad guy used evil magic to suck all the oxygen out of the air causing Mario to suffocate. This made just about as much sense as everything else in Super Mario Brothers, so I simply accepted it and moved on. It was only recently that I gave the ticking clock a second thought.

Super Mario Brothers was hardly the only title to feature this fiendish device. In most cases the clock’s presence required no explanation; finish before the time runs out or you die. For example, the developers of the infamous Contra included one; presumably they felt that their game was too easy without one. In some cases players were furnished with at least a thin rationale for the ticking clock’s presence. In the original Prince of Persia, the evil Vizier Jaffar gives the princess one hour to marry him or be killed, thus giving players an incentive to haul ass.

For the most part an actual clock counting away the seconds between life and death has disappeared from games. Occasionally one will show up letting you know how long you have to escape the collapsing tower or save the hostages or whatever else, but only rarely. The ticking clock’s time has run out, we no longer need it to encourage us to progress forward. The new ticking clock is danger. If you decide to rest on your laurels while playing Left 4 Dead 2, it won’t take long until an army of irate zombies shows up to encourage you to move on. If you hesitate before jumping off of a burning truck in Uncharted 2, it goes careening over a cliff and you end up like Wile E. Coyote.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

Real Moral Choice

Monday, November 23, 2009

There’s a Time and a Place

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Most video games are set in one of a few familiar time periods: World War 2, the present day, or the future (usually either of the dystopian or war-torn variety). Many fantasy games are set in what is essentially a mythologized version of medieval Europe or Japan. Very few games step outside these established temporal settings.

This is part of what makes Assassin’s Creed 2 such a breath of fresh air. The title is set in Renaissance-era Italy, complete with some of the most famous landmarks and figures that inhabited it. I spent this weekend climbing to the top of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore and chatting it up with Leonardo da Vinci. There is enough accuracy and detail worked into the game to reach that holy grail of narrative video games: suspension of disbelief. The original Assassin’s Creed was a less polished game, but the strength of the setting was not among its faults. Having seen Ubisoft’s recreations of 12th Century Jerusalem and 15th Century Florence, I can’t wait to see where, and perhaps more importantly when, the Assassin’s Creed games will go next.

Even in games that have very little basis in reality, a change in temporal setting can add a great deal to the experience. Think of the visual style of BioShock: if it hadn’t been set in 1960, the art deco aesthetic and old-fashioned clothing on the splicers might never have been, the songs on the jukebox would have been completely different, and the atmosphere of the game just wouldn’t have felt so fresh. Breaking apart from the typical medieval European fantasy setting, Jade Empire managed to present a unique role-playing game by placing the player in a mythological version of ancient China. It’s no coincidence that the settings of these games are all so well praised. In an industry replete with cookie-cutter worlds, a simple shift in time and place can yield scores of new ideas and experiences.

Think of all the untapped potential on maps and in history books. When will we see a role-playing game based on Egyptian mythology? A western-style shooter in late 19th Century Australia? How about a survival horror game in a factory town in the American Midwest during the Great Depression? Why do we keep revisiting the same times and places, when there is so much more to see and do?

Friday, November 20, 2009

Falling off the Dragon

Oh my god! Is it Friday?

Crap, I think it really is. That would explain why I am at work at least. I don’t understand, what the hell happened? The last thing I remember it was Saturday morning, I was at a Best Buy purchasing a copy of Dragon Age: Origins, but then it’s all a blank. What happened to my week? Why haven’t I shaved? Man, my joints ache like I’ve spent days sitting in an office chair. I’m exhausted, when was the last time I got a full night’s rest? The last time I remember feeling like this was in the middle of my World of Warcraft addiction back in college. This can only mean one thing. I must have had a relapse.

Wait, now I remember. I’ve spent the last week enthralled in Bioware’s latest time vacuum. Oh god, I thought I was past this. Can I really be blamed though? The game play for this title is magnificent, it’s challenging and varied. Success requires tactical considerations and careful planning. The characters are compelling and the voice acting is flawless. And there is a plot, an honest to god plot that I actually find engrossing. Presented with a game that involves a story arc and character development, can I really be blamed for a little slip? Who’s got a problem? You’ve got a problem. Don’t judge me!

Who doesn’t enjoy a good fantasy RPG? You remember Baldur’s Gate right? Dragon Age manages to combine writing in the tradition of Baldur’s Gate with the same playability that has made WoW an international hit. Ask the other bloggers, I am not the only one who thinks so, the net is littered with praise for this title. The familiar landscapes in the game fall a little short for me, but nothing is perfect. See, you see that? I found some fault in the game; I’ve totally got this under control.

Now if you will excuse me, it is Friday afternoon and I need to go home, to uh, walk my cat, I mean brush my plants, no wait I need to water the cats. Yeah, that’s it…

Monday, November 16, 2009

You’re Speaking My Language

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Gamers, like kids and drunks, say the darndest things. Just last night I sat down to play Mario Kart Wii with a few friends. This was only the second time any of us had ever played this incarnation of the game, but we were having a blast just learning the courses and the new power-ups. As we chatted about the mechanics of the game and shouted obscenities at one another, I took note of some of the stranger sentences that sprung unbidden from our mouths:

“I think that if you’re in the air when you get POW’d, you don’t spin out.”

“The lightning storm works like a hot potato! Ram somebody!”

An outsider would surely think us mad, but such is the nature of video games and their effect on language. One of the great beauties of language is its adaptability. Lacking the needed terms to describe a given situation causes players to create their own. When Shakespeare didn’t have a word that worked for one of his plays, he invented one. I’m not saying that words like “POW’d” have quite the same puissance as Shakespeare’s invented words, but they still serve a linguistic purpose. I know that when I played Neverwinter Nights online, terms like PhK and FoD were bandied about, and no one looked askance. We all spoke the same language; our communal terms helped to define us as a community.

(They’re spells, for the curious. Phantasmal Killer and Finger of Death. Both bad news.)

I’ve never played World of Warcraft, and when two of my in-recovery friends speak of their halcyon days in Azeroth they are completely incomprehensible to me. (Chris grows more understandable with each passing day.) I’ve picked up a few words here and there, maybe enough to get around, find a bathroom and even a bite to eat. From the Penny Arcade comic below, for example, I’m pretty sure aggro is aggression and DoT is damage over time. Many gamers use terms like nub, newb or noob to mean someone who is either new to a game or acting like they are. But Omen? Raidwipe? L2P? MT? I need a translator, someone who has walked these lands before. Whether it’s yelling at a friend to use their star power or complaining about shotty spam, video games do more than take us to new locations. They teach us new, bizarre languages and rule sets that only make sense in the context of the game. We talk about the gaming community as a whole, and the communities that arise around specific genres and games, and nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in these communal languages. It’s a testament to the power of video games that this never strikes us as odd: just like our own native languages seem like the norm to us, the languages of the games we play become perfectly natural over time. It’s only when we walk into a room of people playing a strange game that we realize just how bizarre this phenomenon can be.

Whether it’s yelling at a friend to use their star power or complaining about shotty spam, video games do more than take us to new locations. They teach us new, bizarre languages and rule sets that only make sense in the context of the game. We talk about the gaming community as a whole, and the communities that arise around specific genres and games, and nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in these communal languages. It’s a testament to the power of video games that this never strikes us as odd: just like our own native languages seem like the norm to us, the languages of the games we play become perfectly natural over time. It’s only when we walk into a room of people playing a strange game that we realize just how bizarre this phenomenon can be.

So what’s the strangest thing a game has ever driven you to say? Have you ever paused to wonder just how such a sentence left your lips? I know I have.

Friday, November 13, 2009

'Twas the Night Before Starcraft

“Callooh! Callay!” The children shout.

See them dance in the street and flare their little nostrils against the window pane. How very adorable the entire scene is, except this is not a Dickens novel and those are not children, that’s me and Daniel and we are in our mid twenties.

We may not be as cute as we were when we were kids, but unlike our mannerisms, our stance toward vegetables, and our general outlook on life and the world around us, our enthusiasm for video games has refused to grow up even a little bit. Also, who the hell asked you what’s cute? Take a hike, buddy.

There is more to enjoy about video games then just playing them. While that is, of course, their primary function as entertainment, I would put forward that the anticipation is an important part of the fun. In the often humdrum monotony of our adult lives, having a few things that we are genuinely excited about is invaluable. It gives us something to monitor and study that is fun rather than vital to the operations of our lives, like the market or the news. Even after a particular title has been played to its completion and retired, it gives us something to talk about (or write about at great length) for years to come.

This child-like enthusiasm is not without its pitfalls. Along with this juvenile “need” to have a particular title comes a childish tantrum when our desires are not met. For example, ever since Blizzard’s announcement of Starcraft 2 back in the late eighteen hundreds, I have been beside myself with anticipation for its release. True to form, Blizzard has dangled this sumptuous carrot in front of its avid fan base for years now and every time we think it is in biting range, they announce another delay. So far they have been completely un-responsive to my letters claiming that if they don’t finish developing it I will hold my breath until I pass out. Daniel is equally unsympathetic to my woe; every time I pout about this subject he enjoys a hearty laugh at my expense. This is hyperbole of course, but I do feel an irrational frustration that I am forced to wait for this release. It’s the same frustration I felt in 1999 waiting for the original Starcraft, and 1995 waiting for Warcraft 2: Tides of Darkness. That was fourteen years ago, I was twelve, and it still feels exactly the same. It may be frustration, but in all honesty it is a fun sort of frustration.

We fixate on these games; we follow their development with great interest, play them, and then analyze everything about them. And why? Partially because of the reasons we have so often espoused here at Press Pause to Reflect, that video games are a socially important artistic medium worthy of attention and respect. Also, we simply enjoy the act of playing video games. But aside from these reasons, there is the fact that it just feels good to have something in the often dour and serious world of adulthood that makes us feel like kids dancing in the street, excited for the next big thing.

Monday, November 9, 2009

It Takes Two

by C.T. Hutt

by C.T. Hutt

I spent a good portion of this last weekend wandering the dry and desolate plains of Borderlands. Borderlands, like so many other first person shooters, presents gamers with a sea of repetitious enemies, inane quests, and a paper thin storyline set in an all too familiar landscape. To Gearbox Software’s credit, the game does employ an interesting A Scanner Darkly-esque visual style, but Borderlands brings little else to the oversaturated FPS market. Why then was I so content to spend hours this weekend parked on my keister whittling away at my meager quotient of free time? The answer is quite simple: I was playing with a friend.

While Daniel has had the opportunity to play the Xbox Live version of Borderlands with some complete strangers (an experience he affectionately refers to as “Bro”derlands) we are both agreed that the best way to enjoy this game is in off-line co-op mode. Sure, the screen is split which creates some visual challenges, but so what? Exploring Pandora and searching for the next great gun or level up is simply more fun with a buddy.

Even the most mundane mission can be entertaining with some company. Case in point: Your objective is to follow a green dot and pick up a cog so that we can re-start the town’s snow cone maker (I don’t know what we were restarting, I never read the quest descriptions). This quest would be completely boring if it weren’t for my crippling incompetence behind the wheel. When I take a wrong turn and crash our vehicle into an explosive pit filled with monstrous ant spiders, things become more exciting. A one man army firefight is pretty interesting, but we see that in pretty much every FPS. Toss in the dynamics of having to rescue your partner or work together to bring down a colossal foe and the experience becomes much more engaging. Co-operative play makes humdrum games like Borderlands pretty fun and it makes solid games, like the new demo for Left 4 Dead 2, a complete blast.

The NES, Sega, and other Bronze Age consoles bear little in common with the sleek machines which now dominate the market. However, in their enduring wisdom the founding developers made sure that early consoles came with two controller ports. Single player games were fine, but if you ever wanted to get the most out of your system you would need to acquire one thing that not even the most skilled manufacturer can build for you: a companion.

I think this was a very forward-looking move on the part of developers. The best things in life are the ones we share with other people. If video games were ever to attain widespread popularity they would have to evolve to be more inclusive. Challenges abound as, unfortunately, one of the dangers of the video game medium is isolation. On top of the limitations of a split screen, many game genres don’t readily lend themselves to co-operative play. Static storyline RPGs, for example, are almost exclusively a single player affair. Fighting and sports games are, by their definition, a contest rather than a shared effort. Many puzzle games, tower defenders, and even platformers which practically beg for a cooperative element, simply do not have room for more than one gamer at a time.

Fortunately, as the medium matures so has its ability to bring more and more people into the mix. The curious platformer/puzzle game LittleBigPlanet is a fine illustration of how co-operative play has come along; you couldn’t pull moves like that in Super Mario Brothers, no sir.

While I have plenty of gripes about trends in the video game industry (see paragraph 1), I am encouraged to see more high quality games which have a co-operative element. I wish that Borderlands and many games like it would provide a better single player experience but, barring that, I will settle for a well polished cooperative element. Online play with friends is fun too, but it will never replace a timely high-five after you and your friend beat the big boss together.

Friday, November 6, 2009

Fool Me Twice

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

I've been suckered into buying copious amounts of downloadable content for long enough. I purchased Fallout 3 when it first came out (the ridiculously expensive edition that comes with a broken clock), and dutifully bought each additional adventure as it was released. I'd already completed the main storyline, so I waited until all the packs were out to actually play through them. I don't have any problem with the content itself: I think the various additional adventures were well done, and particularly enjoyed the variety they presented in play style, atmosphere and setting. That being said, I felt a bit of a fool when they announced the "Game of the Year" edition of Fallout 3, with all the additional content at the same price point as the original game. I got a lot of enjoyment out of my time with the game, but waiting clearly would have served me better.

I didn't buy LittleBigPlanet when it first came out because I didn't have a Playstation 3. Now I do, and I was lucky enough to get onboard with the "Game of the Year" edition of that game, which comes with a pile of downloadable content already on the game disc. This feels like a small personal success. It's clear that this is becoming the new model for video games with extensive downloadable content plans. Release the game, release the add-ons over a few months, then re-release the game with all the add-ons.

So here comes Dragon Age: Origins, a game that seems specifically designed to empty my wallet. A spiritual successor to Baldur's Gate 2, you say? A dark, epic fantasy inspired by Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire? Be still my heart. The only reason I don't own the super fancy mega edition is because I barely resisted purchasing a brand new computer this month to play the thing. I know I want to play it, my soul cries out for me to play it, but I also know that it will be best on the PC. That's how I experienced the Baldur's Gate games, and that's how I want to experience Dragon Age. Even so, it's hard to resist its siren song.

But there's something soothing my hungry soul. The game has only just released, and there's already paid downloadable content out for it, with a plan for a lot more. To me, this says that one day in the not too distant future, there will be some sort of complete edition, perhaps another "Game of the Year" if it wins any such awards, and by then a computer to run it will be considerably less expensive. I may miss out on the experience for now, but I'll comfort myself with the fact that I wasn't suckered into a long, drawn-out scheme to part me from my money. And when I finally play the game, all those additional quests and dungeons will already be there, rife with possibilities, treasure, and intricate plotlines. There might even be a few dragons left.

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Lay Waste to the Wasteland

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been playing a lot of Borderlands and Brütal Legend. I’ve been having a blast with both, though they represent entirely different schools of game design. The difference lies in the ambitions of each product. Brütal Legend tries to do a lot with mixed results, while Borderlands is more focused and, as a result, better executed.

Borderlands only sets out to do a few things: it wants to be a good first-person shooter, it wants to provide a fun co-operative experience, and it wants to inspire a Diablo-esque fixation with collecting better loot and leveling up. It does all that, and looks great besides, with a visual style torn straight out of a comic book. My expectations were met almost perfectly. Even the story, what little there is of it, seems to fit the mood of the game: your character is a vault hunter, seeking lost riches and artifacts on an alien world, and you spend most of your time in the game gathering riches, weapons, and other treasures. You’re looking for treasure so you can find more treasure. That’s the game in a nutshell. The game becomes repetitive, but no more so than Diablo and its sequel. It’s a winning formula.

Brütal Legend has no such focus; it wants to do everything. Set in the ancient, mythical land of heavy metal, it starts as an action game, with an axe for melee attacks and a guitar calling down lightning and pyrotechnics on enemies. Combos are learned, weapon upgrades are purchased. Only then it’s a driving and shooting game, complete with speed boosts, ramps and on-board machine guns. This transitions into an open world exploration game, with plenty of collectibles to find. Sometimes it’s a rhythm game, where a quick Guitar Hero-style solo can be used to raise an ancient relic from the ground or literally melt the faces of your enemies. Then come the strategy elements, which range from ordering a few minions around on a mission to full-blown real-time strategy mayhem, complete with troop upgrades and resource management. These are called stage battles, and your resources are your fans, which rise up from the ground when they hear the presence of heavy metal.

It’s a very creative game, and it overflows with incredible moments. I discovered a guitar solo, for example, which summons a flaming zeppelin from the sky to crash and explode wherever you’re standing. That’s just as awesome as it sounds. The environments are as face-melting as the solos, from walls of amps set into craggy cliff faces to mountains of bone and ice, with trees made of hot rod tailpipes. And the writing is fantastic in its variety as well: the game is inspiring, sad, dramatic and hilarious, all in turn or occasionally at once.

In playing both Brütal Legend and Borderlands, I found myself wondering which school of thought resulted in a better game. Borderlands is a much more polished experience, to be sure, and some of the different gameplay modes in Brütal Legend fell a little flat, though I enjoyed the real-time strategy elements more than I expected to. Borderlands, however, offers very little in the way of variety. The game is played the same way throughout, there are only a few types of enemies, and the majority of the game takes place in cracked desert wastelands. Borderlands is a very satisfying game, but in many ways Brütal Legend is a more exciting one. The game is laced with madness, humor, and drama, and there are new and exciting ideas around every (flaming, metallic) corner. It may not succeed at everything it tries, but it does so many different things that it hardly matters. I’ve really been enjoying Borderlands, but I think that Brütal Legend has a lot more to offer. Borderlands will feel familiar, while Brütal Legend will surprise you. And looking back on the games I’ve loved, it’s those memorable, surprising moments that withstand the test of time.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Play by the Sword

By C.T. Hutt

By C.T. Hutt

When I was about five years old, my grandmother read me Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island in its entirety. That very year, my older brother loaned me J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series when he was finished with them. I was hooked: as long as there was a chance of high adventure and sword play, I was willing to stick my nose into almost any book. My enthusiasm for swords and sword fighting was not limited to the literary world. Growing up on a farm, kids have to make their own fun and my brother and I did so in fine style. We spent entire summers hammering crude cross handles and makeshift shields out of scrap wood scavenged from the workshops and barns in the area. Our weapons made, we would battle for hours, smashing away at each other’s faux weapons until they broke or we were called in for dinner. We must have put my mother through no shortage of worry, but it was fun, some of the best fun I’ve ever had.

It is no surprise that video games were quick to tap into young peoples’ interest in medieval armaments and fantasy. The Legend of Zelda was a huge success, and with good cause. In its time, it had awesome graphics and brilliant game play. These qualities where all but lost to me at the time as I was much more concerned with the sheer awesomeness of not only getting to see a dragon on my TV screen, but getting to slay it with my own hands. Other titles like Ninja Gaiden and the first couple of Final Fantasy games also grabbed my attention early on. They were, after all, adventure stories involving swords, and that was enough for me. The 1987 release of Sid Meier’s Pirates! Included not only a sword fight mini-game but scurvy buccaneers as well; you better believe I played that game through a couple hundred times on my parents’ old Mac.

Flash forward to the late nineties, my cup runneth over. Innumerable RPGs littered the medium; the Samurai Showdown and Last Blade series made a splash in the fighting game scene, and strategy games like Warcraft put entire armies of blade-wielding minions at my disposal. Weapons were upgradable; some of them glowed with magical power, and some of the best RPG’s like Bioware’s Baldur's Gate even allowed you to build a character from the ground up to specialize in almost any conceivable armament. It was a golden age of the controller and the sword, yet still, I was not satisfied. I wanted more from the experience.

It’s not that any of these titles fell short of video game greatness; they just never quite hit swordplay greatness. The player hits a button or clicks a mouse and the avatar swings a sword, damage is then assigned with a numerical representation displayed in a health bar. It just wasn’t enough: guns are a point and click mechanism, hence the enormous successes of ever so many first person shooters, but swords are much more complex. A gun shoots in one direction at a time; the swing of a sword is a much more elegant piece of physics. Its lethality is not only based on where it hits its target, but how fast it is moving, and how much weight you’ve put behind it. I can certainly appreciate the difficulty of putting such considerations into programming language, but without them I feel that the medium hasn’t quite captured the experience yet.

There have been several notable exceptions. Square Soft’s 1998 release of Bushido Blade 2 made a big impression on me. It was not so different from most of the other early 3-D fighting games with two major exceptions: one, your characters were armed. Two, if you managed to score a good hit on the other player with your weapon, they died. Even between two skilled opponents, matches typically lasted less than fifteen seconds. Many people didn’t like this kind of pacing, but I thought it was brilliant. After all, in the real world, if someone slashes you with a katana, it tends to kill you. Also in 1998, the developers at Tantrum Entertainment released Die by the Sword, a platform adventure game where you controlled the actual movement of your avatar’s sword arm, allowing you to thrust, parry, and slice to your heart’s content. This was a brilliant addition to the game, but a difficult dynamic to master. Translating complex swordplay to the keyboard never quite panned out. Both of these titles fell by the wayside of video game deployment, but I felt they had important things to offer the medium.

In 2006, I watched demonstrations of the Nintendo Wii and felt a new glimmer of hope. Here was perhaps the greatest development in gaming since the turn of the millennium. With motion-sensitive controls our avatars now not only responded to the manipulations of buttons and joysticks but the movements of our bodies. A crucial gap between gamers and the worlds they explore had been bridged. Playing the original Wii Sports I couldn’t help but think: if this system lets me toss around a bowling ball, what’s to say it won’t let me swing a sword? The release of Zelda: Twilight Princess got me all aflutter, but the end result was something of a disappointment. Sure, you swing your arm and Link swings his sword, but only in a few different ways. So far, swordplay on the Wii hasn’t really come into its own. Developers haven’t yet put all of the pieces together.

Hope springs eternal. Red Steel 2 for the Nintendo Wii is due for release in the first quarter of 2010 and it promises to utilize the full potential of the Wii MotionPlus, which should help sword play feel more like sword play and less like hitting buttons. Until then I will just have to goad my brother into a stick fight when we get together for Thanksgiving.

Monday, October 26, 2009

When Marketing Ploys Go Bad

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

As a role-playing game fanatic, it is safe to say that Dragon Age is one of my most anticipated games releasing this fall. I've enjoyed every BioWare game that I've played thus far, and been very impressed with their other original properties, Jade Empire and Mass Effect. So naturally, when I saw that they have a free flash-based game, presumably to whet the public's appetite with a taste of the setting and story, I decided I would give it a spin.

The game, Dragon Age: Journeys, is a fairly basic point-and-click affair with a simple turn-based combat system. It's nothing fancy, but one doesn't expect much from a free flash-based game on the internet. But having played the game to its completion, I find myself much more nervous for Dragon Age: Origins than I was before. Previously, I was going to pre-order the game. Now I think I'll wait to read a few reviews.

Why such a sudden change of heart, based solely on flash game? Simply put, the writing and plot are terrible. I understand low production values on a flash game. Things like a simple interface, basic combat, and uninspired gameplay are pretty much par for the course in the realm of free games you can play in your browser, especially games that are meant as promotional tools. But what I really expect from a BioWare game is good writing and an interesting plot, and there's no reason that the flash game could not fulfill the basic function of making the world of Dragon Age seem interesting. Let me give you an example of the dialogue in this game:

Dwarf: "We found only you at the gates of Orzammar, wounded, dazed, and rambling."GLOWING. That's actual dialogue! This isn't just one tiny example out of the whole game, either. You spend the majority of this game talking to people about how you saw a guy who glowed blue. They don't even try to make it sound more interesting than that. You'll walk up to characters and say things like, "We have to see the king! He needs to hear about this glowing blue darkspawn!"

PC: "We ran into an emissary. He seemed different. He was... glowing?"

Dwarf: "Glowing you say? I've never heard of such a darkspawn."

I'm sure this game wasn't written by the lead writing team of Dragon Age: Origins. In fact, the game may not have even been touched by BioWare, but rather handled entirely by some other branch of Electronic Arts. But what's the point of a flash-based Dragon Age if not to show how interesting the setting and plot will be? We certainly don't come to browser games like these for the incredible 3D graphics and console-like gameplay.

At the end of the game, there was a questionnaire which asked how much I would be willing to pay for the continuation of the game, either online or on the DS or iPhone. I'm not sure I'd play it even if it were as free as the current game. I honestly don't want to know what happens with the sinister blue glowing guy. It's discoloring all my thoughts about a game I'm very excited about.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Barefoot in the Snow, Uphill Both Ways

by C.T. Hutt

by C.T. Hutt

About a week ago I had the opportunity to replay Earthworm Jim. (For you young ‘uns out there, Earthworm Jim is a side-scrolling platform game released by Shiny Entertainment back in 1994.) Back in the day, when I was adorned with a stylish half-mullet and denim jacket, I rocked this game in a single weekend. Playing a week ago I was surprised to find two things: one, the humor and graphics for this title are still very enjoyable. Two, I had no ability to play it.

I wasn’t too surprised at first; the gameplay for older games is notoriously difficult. Still, there was a time during my tenure as a gamer when I was able to overcome these challenges. Have I lost my touch? Have I become so dependent on modern controls that I no longer have the skills? I beat Mike Tyson’s Punch-out for god sake, I threaded the needle in the bike level in Battletoads, I delivered to the entire neighborhood in Paperboy (more examples here); I was a champion I tell you, one of the best. Can it be that at twenty six I have already passed my gaming prime? The sad answer is probably yes. But there is no denying that it is not only me that has changed, it’s the medium as well. While this is hardly a great revelation, I believe there are really two significant evolutions in gaming that separate the difficulty of modern games from the difficulty of classic games.

Programming

In the classic side scrolling shooter Contra things are not so equitable. Enemy spawns are pre-set, but just random enough so that occasionally, in the constant flurry of bullets, fireballs, and pointy sticks your avatar will find themselves in a position where no amount jumping, ducking, or dodging will save you. Call it “extreme difficulty” if you want to, but I chalk up this kind of scenario to poor design.

Newer games have embraced a gentler learning curve than the classic games that I grew up on. Games that introduce challenge steadily, allowing the player to adapt along with the gameplay, have become the gold standard of the modern age of gaming. A few games had this right from the start: most notably, Super Mario Bros. and other early Nintendo titles showed a very forward-thinking design aesthetic and learning curve. But for the most part, games beat us to a pulp and we liked it, because that’s the way it was.

The classic games that I grew up on had many other limitations, but I would never slight their contribution to the medium. While I may have grown soft in my “old” age, I am continually impressed at how far interactive media has progressed. Programmers of classic games did the best they could with what they had, and while their games may be nearly impossible by today’s standards I do take a measure of pride that I got to play them in their heyday. I may not be able to tell my grandchildren that I fought in a great war or endured an economic depression (although we are pretty close), but I will be able to tell them that I was there at the very beginning of an artistic revolution.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Hollywood Game Design: The Cinematic Experience of Uncharted 2

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Uncharted 2: Among Thieves is the best movie-based video game of all time. While it isn’t based on a specific movie, it is an overt homage to the action-adventure cinematic experience in general. With well-written characters, riveting action set pieces, and jaw-dropping cinematography, the game’s ultimate success is that the player walks away thinking, “I just saw the best action movie of the year, and I played the star.”

Uncharted 2 offers interactivity in terms of how you reach your goals: you can use stealth or action, attack a situation in a variety of ways, and clamber over half of the environment. But no matter how you play the game, the results are always the same. This is always the case in games with linear plots, and the approach serves Uncharted 2 well. While the game doesn’t capitalize on the ultimate potential of interactive entertainment, the linearity allows the game an incredible sense of focus. The characters are likeable and well-defined, and each scene plays out beautifully. The mechanics of the game are all well-realized: the jumping and climbing functions just as well scaling a cliff face as it does jumping from truck to truck as they race along a snowy mountain side.

(Mitch Krpata, of Insult Swordfighting, makes some excellent points about the focus of the game and what they must have omitted here.)

Uncharted 2 accomplishes something that video game designers have been striving to do for years: it successfully captures all the drama, excitement and fun of a big-budget action-adventure movie. The additional interactivity makes it even better than a Hollywood blockbuster, because any accomplishment that Drake enjoys is the player’s, as well. Uncharted 2 is a fantastic game, but its power is in its execution, not any form of innovation. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, but I hope that it motivates other developers to branch off in different directions entirely.

There are a few schools of thought on how to make video games. With Uncharted 2, Naughty Dog has conquered the Hollywood school of game design, focusing on characters, linear stories and epic action. Uncharted 2 is the new gold standard, and Naughty Dog has charted the path to success in games that feel like movies. There are other realms to explore and innovations to discover in video games, but they lie down different paths.

Friday, October 16, 2009

All You Need is Love

“I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people”

Vincent Van Gogh

Mario, Zelda, Prince of Persia, Super Ghouls and Ghosts etc.

Life is good, some terrible lizard/dark wizard/grand vizier kidnaps your significant other and puts legions of baddies and dire puzzles in your path. You are on a quest to get them back. Ever since Donkey Kong couldn’t keep his hands to himself, this well-worn love story has been a video game staple. A protagonist needs a reason to head out his or her front door and a kidnapped lover seems like a pretty clear one. From a writing standpoint this approach to a plotline is extraordinarily easy. The love between the characters is present throughout the entire game, but never has to be developed because they never spend any time together. In the end the two lovers smooch, cake is exchanged (wink), and all is well. This depiction of love in video games is childish and easily forgotten; it’s meant to be.

Max Payne, Gears of War 2, The Darkness, etc.

Life is good, some terrible crime lord/horde of gun-toting orcs/shadowy government organization kills your significant other and puts legions of baddies and dire puzzles in your path. You are on a quest to kill them, kill them all. Again, love here is not being used as a centerpiece of a great work, but rather as a moral excuse for letting the protagonist pull the trigger several thousand times. While there is certainly some truth in the idea that a lost love can be a powerful motivator for personal change and that tragedy walks hand in hand with the desire for destruction and revenge, these philosophical considerations are almost universally lost in video games. I will grant that in its noir-tastic dialogue the Max Payne series does a fairly artful job of addressing the sort of self-destruction inherent in a revenge story, but such musings are drowned out by constant gunfire. The plotlines of these games and their portrayal of love are often laughable no matter how much fun it is to shoot gangsters.

Baldur’s Gate, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic 2, Mass Effect, The Witcher, Fable

Role Playing Games have a distinct advantage in portraying the full pallet of human emotions, including love. Unlike more action oriented games, RPG’s constantly ask us to pause and consider our actions before deciding on the best course. In battle, this means selecting the optimum plan of attack, in plot, this means talking with non-player characters and choosing your words carefully. When selecting dialogue options to progress the story, some developers have chosen to add romantic plotlines to the mix. I believe that this approach to portraying love in video games shows great promise. By utilizing the medium’s most definitive characteristic, interactivity, as a method of exploring romance and all the glories and pitfalls therein, I think that developers have a better chance of portraying love in a unique way.

However, this approach is not without its drawbacks. In The Witcher, the player’s avatar can choose to pursue a monogamous relationship or to enjoy a romp with as many NPCs as possible. Sexual congress in the game is symbolized by tarot card-like pictures which can lead to a rather adult themed “Gotta catch ‘em all” mentality in the gamer which I feel devalues its attempts to portray serious relationships. Similarly in Baldur’s Gate 2: Shadows of Amn and KOTOR 2 only one romantic relationship can be successfully realized per play through. By playing through the game multiple times the main character can explore all possible relationships. Again, I feel this detracts from the writers’ and developers’ attempts to express the drama of serious love in relationships. Of course, in the real world there are many fish in the sea and love is terribly complicated, but by allowing such a variety of relationships in a single game developers lose their control of the story. While I think this approach has great potential, for the time being I think it makes video games feel less like Orpheus and Eurydice and more like Leisure Suit Larry.

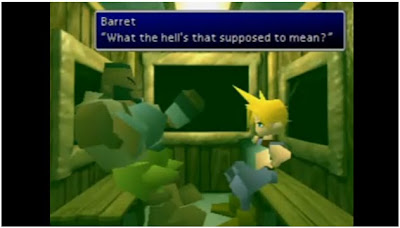

Final Fantasy

In terms of RPG’s with static storylines, the Final Fantasy series has long occupied a place of prestige . While there is no continuous plotline in this iconic series, a gamer can always be certain to see two things: an airship and a love story. And while the translations may be mediocre and the characters may be overblown, I have to give the series its proper due in terms of the variety of love stories it incorporates. In some cases characters with opposing personalities wind up together (FFVIII), in some love is lost early on only to be found again later (FFVII), in still others love is tragically split apart in the end (FFX (admittedly it is recovered in the abominable FFX-2)). The stories are reasonably engaging and the games built around them are great fun. Still, I don’t think any of the series has produced a real showstopper. Perhaps it’s only a matter of time until they do.

Shadow of the Colossus

Shadow of the Colossus is one of the blue ribbon babies for those who see video games as art. Whenever naysayers claim that the medium is nothing more than a vehicle for petty entertainments we can point at Sony’s 2005 release and say, “In your face, my good sir.” In addition to being visually stunning and fun to play, Shadow of the Colossus centers around a touching, albeit tragic, love story. With his true love at death’s door the protagonist overcomes impossible odds striving to bring her back. As the game progresses it becomes evident how much this quest will cost him as the man he was morphs into a twisted personification of his own grief and pain. I believe that the only reason Shadow of the Colossus is not widely recognized as great art is because of the stigma surrounding the video game medium. Truly, it was ahead of its time. Perhaps, as video games spread to a greater proportion of the populace this game will receive the recognition I believe it deserves. Time, I suppose, will tell.

As the artistic medium of gaming continues to evolve I imagine that more developers, both independent and incorporated, will begin to more fully realize the awesome potential that video games have to express truth about the human condition. With that realization I am sure we will see more titles that use love and relationships not just as motivations or side notes but as central themes.