By C.T. Hutt

By C.T. Hutt

When I was about five years old, my grandmother read me Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island in its entirety. That very year, my older brother loaned me J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series when he was finished with them. I was hooked: as long as there was a chance of high adventure and sword play, I was willing to stick my nose into almost any book. My enthusiasm for swords and sword fighting was not limited to the literary world. Growing up on a farm, kids have to make their own fun and my brother and I did so in fine style. We spent entire summers hammering crude cross handles and makeshift shields out of scrap wood scavenged from the workshops and barns in the area. Our weapons made, we would battle for hours, smashing away at each other’s faux weapons until they broke or we were called in for dinner. We must have put my mother through no shortage of worry, but it was fun, some of the best fun I’ve ever had.

It is no surprise that video games were quick to tap into young peoples’ interest in medieval armaments and fantasy. The Legend of Zelda was a huge success, and with good cause. In its time, it had awesome graphics and brilliant game play. These qualities where all but lost to me at the time as I was much more concerned with the sheer awesomeness of not only getting to see a dragon on my TV screen, but getting to slay it with my own hands. Other titles like Ninja Gaiden and the first couple of Final Fantasy games also grabbed my attention early on. They were, after all, adventure stories involving swords, and that was enough for me. The 1987 release of Sid Meier’s Pirates! Included not only a sword fight mini-game but scurvy buccaneers as well; you better believe I played that game through a couple hundred times on my parents’ old Mac.

Flash forward to the late nineties, my cup runneth over. Innumerable RPGs littered the medium; the Samurai Showdown and Last Blade series made a splash in the fighting game scene, and strategy games like Warcraft put entire armies of blade-wielding minions at my disposal. Weapons were upgradable; some of them glowed with magical power, and some of the best RPG’s like Bioware’s Baldur's Gate even allowed you to build a character from the ground up to specialize in almost any conceivable armament. It was a golden age of the controller and the sword, yet still, I was not satisfied. I wanted more from the experience.

It’s not that any of these titles fell short of video game greatness; they just never quite hit swordplay greatness. The player hits a button or clicks a mouse and the avatar swings a sword, damage is then assigned with a numerical representation displayed in a health bar. It just wasn’t enough: guns are a point and click mechanism, hence the enormous successes of ever so many first person shooters, but swords are much more complex. A gun shoots in one direction at a time; the swing of a sword is a much more elegant piece of physics. Its lethality is not only based on where it hits its target, but how fast it is moving, and how much weight you’ve put behind it. I can certainly appreciate the difficulty of putting such considerations into programming language, but without them I feel that the medium hasn’t quite captured the experience yet.

There have been several notable exceptions. Square Soft’s 1998 release of Bushido Blade 2 made a big impression on me. It was not so different from most of the other early 3-D fighting games with two major exceptions: one, your characters were armed. Two, if you managed to score a good hit on the other player with your weapon, they died. Even between two skilled opponents, matches typically lasted less than fifteen seconds. Many people didn’t like this kind of pacing, but I thought it was brilliant. After all, in the real world, if someone slashes you with a katana, it tends to kill you. Also in 1998, the developers at Tantrum Entertainment released Die by the Sword, a platform adventure game where you controlled the actual movement of your avatar’s sword arm, allowing you to thrust, parry, and slice to your heart’s content. This was a brilliant addition to the game, but a difficult dynamic to master. Translating complex swordplay to the keyboard never quite panned out. Both of these titles fell by the wayside of video game deployment, but I felt they had important things to offer the medium.

In 2006, I watched demonstrations of the Nintendo Wii and felt a new glimmer of hope. Here was perhaps the greatest development in gaming since the turn of the millennium. With motion-sensitive controls our avatars now not only responded to the manipulations of buttons and joysticks but the movements of our bodies. A crucial gap between gamers and the worlds they explore had been bridged. Playing the original Wii Sports I couldn’t help but think: if this system lets me toss around a bowling ball, what’s to say it won’t let me swing a sword? The release of Zelda: Twilight Princess got me all aflutter, but the end result was something of a disappointment. Sure, you swing your arm and Link swings his sword, but only in a few different ways. So far, swordplay on the Wii hasn’t really come into its own. Developers haven’t yet put all of the pieces together.

Hope springs eternal. Red Steel 2 for the Nintendo Wii is due for release in the first quarter of 2010 and it promises to utilize the full potential of the Wii MotionPlus, which should help sword play feel more like sword play and less like hitting buttons. Until then I will just have to goad my brother into a stick fight when we get together for Thanksgiving.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Play by the Sword

Monday, October 26, 2009

When Marketing Ploys Go Bad

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

As a role-playing game fanatic, it is safe to say that Dragon Age is one of my most anticipated games releasing this fall. I've enjoyed every BioWare game that I've played thus far, and been very impressed with their other original properties, Jade Empire and Mass Effect. So naturally, when I saw that they have a free flash-based game, presumably to whet the public's appetite with a taste of the setting and story, I decided I would give it a spin.

The game, Dragon Age: Journeys, is a fairly basic point-and-click affair with a simple turn-based combat system. It's nothing fancy, but one doesn't expect much from a free flash-based game on the internet. But having played the game to its completion, I find myself much more nervous for Dragon Age: Origins than I was before. Previously, I was going to pre-order the game. Now I think I'll wait to read a few reviews.

Why such a sudden change of heart, based solely on flash game? Simply put, the writing and plot are terrible. I understand low production values on a flash game. Things like a simple interface, basic combat, and uninspired gameplay are pretty much par for the course in the realm of free games you can play in your browser, especially games that are meant as promotional tools. But what I really expect from a BioWare game is good writing and an interesting plot, and there's no reason that the flash game could not fulfill the basic function of making the world of Dragon Age seem interesting. Let me give you an example of the dialogue in this game:

Dwarf: "We found only you at the gates of Orzammar, wounded, dazed, and rambling."GLOWING. That's actual dialogue! This isn't just one tiny example out of the whole game, either. You spend the majority of this game talking to people about how you saw a guy who glowed blue. They don't even try to make it sound more interesting than that. You'll walk up to characters and say things like, "We have to see the king! He needs to hear about this glowing blue darkspawn!"

PC: "We ran into an emissary. He seemed different. He was... glowing?"

Dwarf: "Glowing you say? I've never heard of such a darkspawn."

I'm sure this game wasn't written by the lead writing team of Dragon Age: Origins. In fact, the game may not have even been touched by BioWare, but rather handled entirely by some other branch of Electronic Arts. But what's the point of a flash-based Dragon Age if not to show how interesting the setting and plot will be? We certainly don't come to browser games like these for the incredible 3D graphics and console-like gameplay.

At the end of the game, there was a questionnaire which asked how much I would be willing to pay for the continuation of the game, either online or on the DS or iPhone. I'm not sure I'd play it even if it were as free as the current game. I honestly don't want to know what happens with the sinister blue glowing guy. It's discoloring all my thoughts about a game I'm very excited about.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Barefoot in the Snow, Uphill Both Ways

by C.T. Hutt

by C.T. Hutt

About a week ago I had the opportunity to replay Earthworm Jim. (For you young ‘uns out there, Earthworm Jim is a side-scrolling platform game released by Shiny Entertainment back in 1994.) Back in the day, when I was adorned with a stylish half-mullet and denim jacket, I rocked this game in a single weekend. Playing a week ago I was surprised to find two things: one, the humor and graphics for this title are still very enjoyable. Two, I had no ability to play it.

I wasn’t too surprised at first; the gameplay for older games is notoriously difficult. Still, there was a time during my tenure as a gamer when I was able to overcome these challenges. Have I lost my touch? Have I become so dependent on modern controls that I no longer have the skills? I beat Mike Tyson’s Punch-out for god sake, I threaded the needle in the bike level in Battletoads, I delivered to the entire neighborhood in Paperboy (more examples here); I was a champion I tell you, one of the best. Can it be that at twenty six I have already passed my gaming prime? The sad answer is probably yes. But there is no denying that it is not only me that has changed, it’s the medium as well. While this is hardly a great revelation, I believe there are really two significant evolutions in gaming that separate the difficulty of modern games from the difficulty of classic games.

Programming

In the classic side scrolling shooter Contra things are not so equitable. Enemy spawns are pre-set, but just random enough so that occasionally, in the constant flurry of bullets, fireballs, and pointy sticks your avatar will find themselves in a position where no amount jumping, ducking, or dodging will save you. Call it “extreme difficulty” if you want to, but I chalk up this kind of scenario to poor design.

Newer games have embraced a gentler learning curve than the classic games that I grew up on. Games that introduce challenge steadily, allowing the player to adapt along with the gameplay, have become the gold standard of the modern age of gaming. A few games had this right from the start: most notably, Super Mario Bros. and other early Nintendo titles showed a very forward-thinking design aesthetic and learning curve. But for the most part, games beat us to a pulp and we liked it, because that’s the way it was.

The classic games that I grew up on had many other limitations, but I would never slight their contribution to the medium. While I may have grown soft in my “old” age, I am continually impressed at how far interactive media has progressed. Programmers of classic games did the best they could with what they had, and while their games may be nearly impossible by today’s standards I do take a measure of pride that I got to play them in their heyday. I may not be able to tell my grandchildren that I fought in a great war or endured an economic depression (although we are pretty close), but I will be able to tell them that I was there at the very beginning of an artistic revolution.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Hollywood Game Design: The Cinematic Experience of Uncharted 2

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

Uncharted 2: Among Thieves is the best movie-based video game of all time. While it isn’t based on a specific movie, it is an overt homage to the action-adventure cinematic experience in general. With well-written characters, riveting action set pieces, and jaw-dropping cinematography, the game’s ultimate success is that the player walks away thinking, “I just saw the best action movie of the year, and I played the star.”

Uncharted 2 offers interactivity in terms of how you reach your goals: you can use stealth or action, attack a situation in a variety of ways, and clamber over half of the environment. But no matter how you play the game, the results are always the same. This is always the case in games with linear plots, and the approach serves Uncharted 2 well. While the game doesn’t capitalize on the ultimate potential of interactive entertainment, the linearity allows the game an incredible sense of focus. The characters are likeable and well-defined, and each scene plays out beautifully. The mechanics of the game are all well-realized: the jumping and climbing functions just as well scaling a cliff face as it does jumping from truck to truck as they race along a snowy mountain side.

(Mitch Krpata, of Insult Swordfighting, makes some excellent points about the focus of the game and what they must have omitted here.)

Uncharted 2 accomplishes something that video game designers have been striving to do for years: it successfully captures all the drama, excitement and fun of a big-budget action-adventure movie. The additional interactivity makes it even better than a Hollywood blockbuster, because any accomplishment that Drake enjoys is the player’s, as well. Uncharted 2 is a fantastic game, but its power is in its execution, not any form of innovation. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, but I hope that it motivates other developers to branch off in different directions entirely.

There are a few schools of thought on how to make video games. With Uncharted 2, Naughty Dog has conquered the Hollywood school of game design, focusing on characters, linear stories and epic action. Uncharted 2 is the new gold standard, and Naughty Dog has charted the path to success in games that feel like movies. There are other realms to explore and innovations to discover in video games, but they lie down different paths.

Friday, October 16, 2009

All You Need is Love

“I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people”

Vincent Van Gogh

Mario, Zelda, Prince of Persia, Super Ghouls and Ghosts etc.

Life is good, some terrible lizard/dark wizard/grand vizier kidnaps your significant other and puts legions of baddies and dire puzzles in your path. You are on a quest to get them back. Ever since Donkey Kong couldn’t keep his hands to himself, this well-worn love story has been a video game staple. A protagonist needs a reason to head out his or her front door and a kidnapped lover seems like a pretty clear one. From a writing standpoint this approach to a plotline is extraordinarily easy. The love between the characters is present throughout the entire game, but never has to be developed because they never spend any time together. In the end the two lovers smooch, cake is exchanged (wink), and all is well. This depiction of love in video games is childish and easily forgotten; it’s meant to be.

Max Payne, Gears of War 2, The Darkness, etc.

Life is good, some terrible crime lord/horde of gun-toting orcs/shadowy government organization kills your significant other and puts legions of baddies and dire puzzles in your path. You are on a quest to kill them, kill them all. Again, love here is not being used as a centerpiece of a great work, but rather as a moral excuse for letting the protagonist pull the trigger several thousand times. While there is certainly some truth in the idea that a lost love can be a powerful motivator for personal change and that tragedy walks hand in hand with the desire for destruction and revenge, these philosophical considerations are almost universally lost in video games. I will grant that in its noir-tastic dialogue the Max Payne series does a fairly artful job of addressing the sort of self-destruction inherent in a revenge story, but such musings are drowned out by constant gunfire. The plotlines of these games and their portrayal of love are often laughable no matter how much fun it is to shoot gangsters.

Baldur’s Gate, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic 2, Mass Effect, The Witcher, Fable

Role Playing Games have a distinct advantage in portraying the full pallet of human emotions, including love. Unlike more action oriented games, RPG’s constantly ask us to pause and consider our actions before deciding on the best course. In battle, this means selecting the optimum plan of attack, in plot, this means talking with non-player characters and choosing your words carefully. When selecting dialogue options to progress the story, some developers have chosen to add romantic plotlines to the mix. I believe that this approach to portraying love in video games shows great promise. By utilizing the medium’s most definitive characteristic, interactivity, as a method of exploring romance and all the glories and pitfalls therein, I think that developers have a better chance of portraying love in a unique way.

However, this approach is not without its drawbacks. In The Witcher, the player’s avatar can choose to pursue a monogamous relationship or to enjoy a romp with as many NPCs as possible. Sexual congress in the game is symbolized by tarot card-like pictures which can lead to a rather adult themed “Gotta catch ‘em all” mentality in the gamer which I feel devalues its attempts to portray serious relationships. Similarly in Baldur’s Gate 2: Shadows of Amn and KOTOR 2 only one romantic relationship can be successfully realized per play through. By playing through the game multiple times the main character can explore all possible relationships. Again, I feel this detracts from the writers’ and developers’ attempts to express the drama of serious love in relationships. Of course, in the real world there are many fish in the sea and love is terribly complicated, but by allowing such a variety of relationships in a single game developers lose their control of the story. While I think this approach has great potential, for the time being I think it makes video games feel less like Orpheus and Eurydice and more like Leisure Suit Larry.

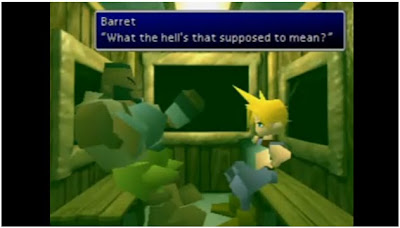

Final Fantasy

In terms of RPG’s with static storylines, the Final Fantasy series has long occupied a place of prestige . While there is no continuous plotline in this iconic series, a gamer can always be certain to see two things: an airship and a love story. And while the translations may be mediocre and the characters may be overblown, I have to give the series its proper due in terms of the variety of love stories it incorporates. In some cases characters with opposing personalities wind up together (FFVIII), in some love is lost early on only to be found again later (FFVII), in still others love is tragically split apart in the end (FFX (admittedly it is recovered in the abominable FFX-2)). The stories are reasonably engaging and the games built around them are great fun. Still, I don’t think any of the series has produced a real showstopper. Perhaps it’s only a matter of time until they do.

Shadow of the Colossus

Shadow of the Colossus is one of the blue ribbon babies for those who see video games as art. Whenever naysayers claim that the medium is nothing more than a vehicle for petty entertainments we can point at Sony’s 2005 release and say, “In your face, my good sir.” In addition to being visually stunning and fun to play, Shadow of the Colossus centers around a touching, albeit tragic, love story. With his true love at death’s door the protagonist overcomes impossible odds striving to bring her back. As the game progresses it becomes evident how much this quest will cost him as the man he was morphs into a twisted personification of his own grief and pain. I believe that the only reason Shadow of the Colossus is not widely recognized as great art is because of the stigma surrounding the video game medium. Truly, it was ahead of its time. Perhaps, as video games spread to a greater proportion of the populace this game will receive the recognition I believe it deserves. Time, I suppose, will tell.

As the artistic medium of gaming continues to evolve I imagine that more developers, both independent and incorporated, will begin to more fully realize the awesome potential that video games have to express truth about the human condition. With that realization I am sure we will see more titles that use love and relationships not just as motivations or side notes but as central themes.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Adapting Literature, According to Visceral Games

Midway upon the journey of our lifeWhen I read that the first section of Dante’s Divine Comedy was being turned into a video game, I responded with cautious optimism. Dante’s Inferno paints an impressive, terrifying vision of hell, and a game set in that world could be compelling. The epic poem was mostly descriptive in nature, so I figured they would have to change a few things to make a more exciting interactive experience. From the first trailer, it looked like they were going to invent some warrior character to go on a quest through hell. It wasn’t too clear.

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

-The first lines of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, Longfellow Translation

When I was still young, but had enough life experience

To be a brooding badass, I was in some freaky place with

Demons and shit and I killed them with a scythe.

-The first lines of Dante’s Inferno, by Visceral Games, Bullard-Bates hypothesis

With each new piece of information that drips out of the offices of Visceral Games, my hopes for the game have dwindled. That warrior from the first trailer, as it turns out, is actually Dante, who is not a 14th century poet but a badass crusading knight. Beatrice, Dante’s dead love in the poem, who serves as a kind of ideal beauty and his guide in the realms of paradise, is captured by the devil and dragged into hell for the sake of the game. Oh, and Dante stole Death’s own scythe, and uses it as a weapon.

What?

I’m not sure what about this disturbs me the most:

But instead of gripe and complain, I thought I might offer up a few other adaptation ideas for Visceral Games, just in case they ever decide to take a stab at another piece of classic literature:1) The people at Visceral Games have taken dramatic liberties with a classic piece of literature to turn it into a generic action game with particularly gruesome backdrops.

2) They could have just as easily made almost the same game without so thoroughly flaying the original by making the main character some invented figure who was not Dante, pursuing some invented figure who was not Beatrice, and leaving out the nonsense about Death’s scythe.

3) If they make any sequels, we might soon see Dante striding into heaven and tearing angels asunder with the horns of Satan, or whatever other silliness they might come up with.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet

In this brutal action-platformer, you take the role of Hamlet, prince of Denmark and heir to the throne. After his father is murdered by a demon that takes the form of his own uncle and claims the kingdom for himself, Hamlet sets out for revenge. Help Hamlet climb the towers of an ancient castle, reclaim the blade Excalibur, and kill the zombie minions of the demon king Claudius!

Milton’s Paradise Lost

After falling from grace, Satan swears revenge. This bloody strategy game pits angel against demon in the struggle for all creation! Mine the pits of hell for the resources necessary to build a demonic army and march on heaven. Build hellish units like the devastating Beelzebub Bomber, stealthy Succubus Assassin, and imposing Legion of Lilith. Once you complete the main storyline, take your game online in a variety of multiplayer modes! Better to reign EVERYWHERE than serve in heaven!

Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment

This first-person shooter stars Rodya, a young russian man with a dark past. Having killed a woman to escape his debts and then discovered that the woman was his mother and left him a fortune in her will, he decides to use his newfound wealth to stamp out injustice wherever he finds it. Using technologically-advanced weapons acquired through the time machine he invents and the supernatural powers which previously lay dormant in his bloodline, Rodya is ready to punish the guilty.

The New New Testament

Jesus was sent by God to kick ass and redeem humanity, and he’s all out of redemption. Jesus returns to earth to find it populated by godless sinners and warmongers, and decides that a second flood might be necessary: a flood of BLOOD. Using the cross he was killed on as a weapon and summoning holy spirits to possess his enemies, he’s going to kill everyone who’s ever sinned. This time, instead of loaves and fishes, Jesus is handing out PAIN.

Feel free to leave your own adaptation ideas in the comments! I look forward to it.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Yeah, That’s the Stuff

Gather 'round gamers, let’s rap. I’d like to talk with you today about a very serious issue in the gaming medium. I’m talking about drugs. And not those harmless street drugs, I’m talking about drugs in video games.

“Now wait a second,” I can hear you say, “I thought drugs were cool.”

Wrong. Drugs are hella lame, and they’re even hella lamer in video games. As we have been told again and again and again everything that happens in video games will eventually translate into real life. That’s why I ride a green dinosaur to work and pick up health kits to replenish my life bar. You see, highly intelligent and up-to-date individuals like politicians and academics know what’s best for you and me, so when they tell us that the portrayal of drug use in video games is a naughty naughty thing, it’s super important that we believe them and lay off the digital smack.

Don’t believe me? Just take it from my man Senator Joe Baca.

“These games allow players to watch strip shows, have simulated sex with prostitutes, assault innocent bystanders, car-jack soccer moms, using illegal drugs, commit mass murder, and kill police officers. There is an increasing amount of scientific evidence that indicates that playing violent video games is positively related to aggressive thoughts and behavior.”

Not only do video games let you use illegal drugs, but they let you use them to car-jack soccer moms! Science says so, debate over.

Thankfully, there are some organizations working hard to censor or penalize developers who choose to portray drug use in video games. Sometimes the benevolent hand of the nanny state steps in to shield us; Fallout 3 for example, was banned in Australia for its portrayal of drug use. In other cases, independent organizations like the ESRB are stamping their ratings on new games as they are released. Simulated drug use is one of several factors along with violence, big boy words, and the sinful exposure of the human body that the ESRB uses to tell us right from wrong. With their help our beloved gaming medium is moving closer and closer to that bastion of moral purity, the movie industry. The awesome thing about third party rating systems and government intervention is that little people like us don’t have to do any of the thinking ourselves. Gnarly!

Now I know some of you may be thinking that drug use in video games is really no big deal. Many of you have been popping pills as Pac-Man or going on mushroom trips with Mario for years. It may seem innocent enough to juice up your Marines in Starcraft with a quick stim-pack, but before you know it you’re going to find your avatar in some ramshackle thieves’ guild in the Imperial City of Tamriel snorting lines of Skooma off the ass of some burned-out Khajiit. Trust me, I’ve been there. It’s not pretty. Thankfully, there are steps that even normal people like us can take to limit the dangers of drug use in video games. First avoid these little-known games that involve drug use or have references to drug use:

Bioshock, Starcraft, Super Mario World, Left 4 Dead, Grand Theft Auto, Oblivion, Fallout 3, Pac-Man, Hitman, Manhunt, Silent Hill, Sam & Max, inFamous, Leisure Suit Larry, Far Cry 2, Twisted Metal, Final Fantasy Tactics, Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell, Max Payne, and so on.

Also, if you see drug use in a video game, tell an adult right away. If you are an adult, flush the game down the nearest toilet.

There may be absolutely no evidence that drug use in video games leads to drug use in real life, but with a little moral indignation and some good old-fashioned panic we can keep our kids and ourselves safe. Remember, gamers, only losers are users.

Monday, October 5, 2009

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jimmy Fallon

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

I never much cared about Jimmy Fallon. He seems a nice enough guy, but he never stood out to me as a comedian. He got a late night show, and this meant nothing to me. (Well, I was amazed to find out that The Roots are his house band, since they're incredible.) But then something interesting happened. First, he had Kudo Tsunoda on the show to talk about Project Natal. Still, it seemed like a one time thing, and Natal seems like the sort of video game project that would have mainstream appeal.

On October 2, 2009, Jimmy Fallon won me over. Tim Schafer, the man behind Psychonauts and one of the people responsible for The Secret of Monkey Island, was one of the headline guests on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. Not only did Fallon have such a great figure in video games on the show, he offered up a sort of mission statement for his show: that they want to treat video game releases like movie openings. He even likens Tim Schafer's name on the cover of Brütal Legend to saying that a movie is a Martin Scorsese film.

Consider me impressed. This is the sort of mainstream attention and respect that video games should be getting, especially as the industry grows to rival that of music and film. I'm glad to see Tim Schafer on a late night show, and I'm grateful to Jimmy Fallon and his team for having the presence of mind to put him there. Who would have guessed that the star of Taxi would one day have his finger so firmly on the pulse of the modern audience?

Friday, October 2, 2009

The Charming Sociopath

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

by Daniel Bullard-Bates

I recently played through Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, and what the critics say is true: it is a very well constructed game, and the animations, characters and voice actors are superb. It did, however, leave me with an unsettled feeling in the pit of my stomach. After all, here was charming, likeable Nathan Drake and his lovely companion Elena, who moved and spoke like real, friendly people I might want to hang out with, looked more realistic than most other video game characters, and killed countless human beings without hesitation or remorse.

This problem runs rampant in video games: because of the genre of a game or the standards set by games that came before, all the hard work put into characterization is thrown out the window in favor of overused tropes. Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune attempts to bring an experience to the console that is as close as possible to a high quality action/adventure film, but even in Indiana Jones’s wildest adventures, he never killed as many thugs as Nathan Drake does within the first few hours of Uncharted. This works against all the hard work put into the character of Nathan. It’s hard to believe that a man who kills so easily is also charming and likeable.

But this is an action/adventure game, and action/adventure games generally pit the player against a lot of enemies. When the mass slaughtering is done by a character like Kratos or Marcus Fenix, it seems more natural because these men are ridiculous stereotypes of action heroes. They are grim, unpleasant, murderous clichés. With a realistic character in the forefront, however, this behavior strikes a more discordant note.

There are simple changes which could have made this disconnect less jarring. One solution would have been to cut down on the number of enemies Nathan Drake faced on his adventure. The game repeatedly recycles combat arenas by sending second and third waves of enemies into the room after each group is dispatched. This made many of the action sequences longer than necessary and increased the body count considerably. Even if every man he killed was actively trying to kill Nathan (and they were), you'd think that when a person loses count of the human beings they’ve killed it might affect their sunny disposition.

Another approach might have been to simply slow down the pace of the confrontations. Enemies do not hide behind barriers for very long, always pushing forward to flank Nathan and his companions. They do not hesitate, retreat, regroup or try to find aid. A group of enemies enters an area, takes cover, moves in to attack, and dies. If they behaved more like they valued their own lives, it could have extended the gameplay and added tension. Maybe they could have even, just every once in a while, presented a character who realized that twelve of his well-armed friends had just been killed and that he was all alone facing their killer. That would be an appropriate time to drop one’s weapon and run like hell, or even surrender, allowing the player an opportunity to show that he is playing a pretty good guy who doesn’t kill unless he has to do so.

I understand that this would make the game a less action-packed affair, and that this would be a concern for the developers. Many consumers look for constant, frenetic action in their games, and Uncharted delivers in that regard. But as games present more realistic, believable characters, questions are raised about whether the gameplay itself detracts from their believability. And when Elena goes from nervously joking about having never fired a gun before to calmly launching explosive rockets at strangers from the back of a jet ski, I must admit that I am a little less in love with the otherwise charming and intelligent leading lady.

There are two philosophies of game design at war here: Uncharted attempts to deliver a lengthy, action-packed experience as well as a fulfilling narrative with a likeable main character. Unfortunately, these two ideas work against one another. This conflict also arises in video game villains, especially those of the malevolently-scheming-behind-the-scenes variety. (Some spoilers for BioShock and Batman: Arkham Asylum follow.)

In the finale of BioShock, the manipulative villain of the game transforms himself into a superhuman monster, despite the fact that it hardly fits the character or the story at all. Why would an enterprising businessman and criminal attempt a direct confrontation? An otherwise excellent, complex and genre-defying shooter, BioShock fell prey to the idea that every video game needs an epic final boss to fight. The result was one of the few flat and uninspired moments in an otherwise stellar game.

Similarly, in Batman: Arkham Asylum, the Joker, who has made a career out of using people like pawns to accomplish his mad schemes, goes out of character and transforms himself into a huge, preposterous mutant to fight Batman directly. Other than in that moment, Arkham Asylum does an excellent job of conveying the Joker as a character, and the translation from comic book to video game was impressive. But the developers wanted a big set piece and an imposing enemy for the finale, so all that careful character development was thrown out the window.

Developers need to realize that it is okay to be different for the sake of a character. A huge, tough boss is all well and good in the right game, but when Batman thwarts the Joker’s plans and defeats his thugs in the comic books, the only thing left to do is to sock him in the jaw and throw him in a cell. For the narrative of a game to improve, the mechanics and gameplay can’t work against the development of the plot and characters. I’d much rather have a great story from beginning to end than have a boss fight just like those in every other game. And if there were a little less killing in Uncharted, I might feel like having a beer with Nathan Drake if I ever met him in a bar. As it stands, though, I think my best bet would be to run for my life.